Ara, our driver and guide, is busy digging his car out of the snow. We drove 167 miles (270 km) the day before and only need another 18 miles (30 km) to reach the highlight of our trip, Tatev Monastery- a secluded medieval monastery in southeastern Armenia near the Iranian border. Overlooking the Vorotan River Gorge, the monastery sits on the edge of a rocky cliff surrounded by lush green mountains. I made a vow that I would visit Tatev after seeing my friends’ Facebook photos, but I am worried that the icy roads will cut our tour short. My friend warned me not to go in November because the weather conditions could be bad. Why didn’t I listen to her? Ara signals over to Erwin, my husband, and me that he is ready to take off. I remain hopeful that we will make it, but then I see the thick fog ahead of us.

The white cloud evaporates as we enter the village of Halidzor. Clothing lines connect the old concrete buildings; only the hanging laundry brings color to the otherwise grey scene. It is a small town with 700 people, and as we drive on its only major road, I notice children playing in the snow, women gossiping, and men shoveling snow off the sidewalks. Life here seems simple; the people look happy. Ara points beyond the village over to the far side of the valley where Tatev Monastery lies on a hilltop plateau. I see a narrow road zigzagging up a snow top mountain and swallow hard because it looks too hazardous to drive on.

I sink down in my seat, disappointed that we won’t see the one place I have been dreaming about for months. Yet, I’m also relieved that we won’t be putting our lives danger.

The Wings of Tatev

Soaring high above the clouds on the Wings of Tatev, I look down at the rural village below. It looks trapped in the snow, completely cutoff from the rest of the world. We are riding on the world’s longest non-stop double track cable car, officially recorded by Guinness World Records on October 23, 2010. The cableway spans 3.5 miles (5.7 km) across the Vorotan River Gorge. At its highest point, the cable car suspends 1,050 ft. (320 m) from the bottom. I feel the car swaying back and forth as we travel about 23 miles per hour (37 km/h). It’s definitely not a ride for those with a fear of heights, but the traditional Armenian music that suddenly starts playing has a calming effect.

Devil’s Bridge

Ara motions for me to look down into the canyon. He points to an ominous crossing called Devil’s Bridge. I assume it received this name because it’s dangerous. Ara explains that it gets its name because no man could possibly build such a bridge; therefore, only the devil could have built it. It is a beautiful natural bridge that people can climb down to relax in the warm springs below and view a wondrous stalactite cave. On the other side are naturally carbonated cool springs – a great place to fill up water bottles in the summer. I am not upset that we chose to avoid this crossing. I feel safer flying up in the clouds than crossing over Devil’s Bridge.

Tatev Monastery

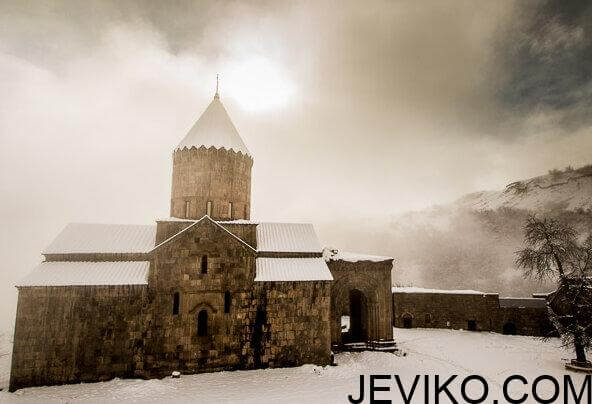

When we exit the car, I finally get my first glimpse of Tatev Monastery. Heavy stone blocks form a formidable wall around the complex – a necessary feature due to the many past Turkish and Persian invasions. Local peasants also carried out several attacks on monastery because they were upset with the monastery’s acquisition of their lands. The fortification today still stands high on the landward side but seems to disappear down the canyon edge. The wall blends so well into sheer rock that it’s difficult to distinguish between two. Mountains covered with snow-dusted trees tower over the monastery, creating a dreamlike setting.

Before the construction Tatev Monastery, the site hosted an ancient pagan temple. It was later replaced by a church when Armenia became the first country to adopt Christianity in the 4th century. It was not until the 9th century that construction on the monastery began. By the 11th century, over 1,000 monks lived at the monastery. The monastery became even more prominent in Armenian culture in the 14th century when it established a university. In addition to attacks on it throughout history, earthquakes have also played a part in damaging Tatev Monastery. It is amazing that Tatev Monastery has survived for more than a thousand years.

Oil Mill

As we approach the entrance, a couple of tourists rush into the monastery, so Ara suggests we check out the 17th Century Oil Mill located outside of the walls. We walk into a small room with a primitive oil mill, or the Dzit-han. It is a huge stone wheel attached to a tree trunk. We notice that Tatev Monastery is not just a beautiful historical and religious site, but it also is an interactive museum. Media presentations stand along an ancient wall, providing information about the culinary and cultural lives of Tatev’s monks. The animation shows monks walking around the pit with the lever to crush flaxseeds, sesames, hemp, and other plants into oil, the Monastery’s main source of income. Erwin cannot resist trying it out. Seeing him struggle to lift the handle, I’m convinced that he was not meant for a monk’s hard life.

Tatev’s Churches

St. Astvatsatsin Church

We finally wander into the courtyard, which besides a few footprints in the snow, is completely undisturbed and deserted. I break the silence by assaulting Erwin with snowballs. He finally has enough; so we follow Ara up the stairs to St. Astvatsatsin Church. Built in 1087, it’s the smallest of the three churches on the Tatev compound. Unfortunately, it is heavily damaged on the inside from rainwater due to poor restorations efforts during the Soviet era.

Since St. Astvatsatsin Church is erected on top of the monastery gate and Grigor Tatevatsi’s mausoleum, it feels more like a fortress tower than a chapel, which inspires Erwin to launch snow-canons from its walkway.

St. Poghos-Petros (St. Paul and Peter) Church

Next, Ara takes us inside St. Poghos-Petros Church, Tatev’s largest building and masterpiece built in 906. Strong aromas of incense immediately fill my nose, and I have to adjust my eyes to the dark. The small windows bring in little light, and only a couple candles hang from above. It’s also cold, but I like that because it’s how I imagine the church would have looked and felt like a thousand years ago. The only thing missing are the beautiful frescos that used to decorate the walls.

St. Grigor Lusavorich (Gregory the Illuminator) Church

We don’t have to walk far to the next church since it’s attached to the St. Poghos-Petros Church. Because of its small size, St. Grigor Lusavorich looks more like a storage room than separate church. I am surprised to learn that it is the foundation of Tatev Monastery. Built in 848 on the exact site of the ancient pagan temple, St. Grigor Lusavorich is Tatev’s first church. The Orbelian Dynasty, however, had to rebuild the church in 1295 when an earthquake destroyed it.

Back view of St. Poghos-Petros Church, attached to it is St. Grigor Lusavorich Church – the small building on the right.

Monk Cells

Monks no longer live here, but we are able to explore the 17th century living quarters, starting with their sleeping accommodations. They look more like prison cells than bedrooms. I peer out of a tiny window to see a magical view of the surrounding mountains, but the view below causes me to catch my breath. Looking down the 2,000 ft. (800 meter) drop to the river gorge below, the monks must have known that there was no escape.

As we further explore the monks’ cells, I notice the rooms got smaller and darker. We reach a small windowless cell less than 43 sq. ft. (4 sq. m). I figure this was reserved for the “bad” monks, but I am wrong… the most highly ranked monks occupied this type of room. The newest monks got the bigger rooms with fireplaces and windows with mountain views. The mid-ranked monks had smaller rooms with windows but no fireplaces. I am confused by this type of system. The monks lost more benefits as they moved up in seniority? At this moment, I realize how much I am enjoying the calm and peaceful atmosphere. So, I rationalize that a monk’s ultimate reward is the escape from the masses and noise of everyday life.

We leave the tranquility of Tatev Monastery and return to the modern world on the Wings of Tatev. The same peaceful Armenian music plays as we glide back over the gorge. We traveled over 185 miles (300 km), and despite all the obstacles we faced in the snow, ice, and fog, we still made it to Tatev. On our drive back to Yerevan, we will stop at the spa town of Jermuk. We plan on hiking down to the waterfall in the Arpa River canyon, another beautiful natural setting. Somehow I know that the rest of our trip will be less eventful and exciting than the journey to Tatev Monastery.